How the Monterey Pop Festival Changed Music Forever

While there's no denying the Woodstock festival's epochal place in the narrative of rock 'n' roll, the Monterey Pop Festival is the one that really altered the way pop culture worked from then on out. In 1967, Monterey Pop represented a beginning for the hippie dream, and two years later, Woodstock ended up being more of a glorious elegy for the waning Aquarian era.

The first real rock festival, the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival in Marin County, actually occurred a week before Monterey on June 10-11, 1967, with an equally impressive lineup. The three-day Monterey fest kicked off on June 16, however, that really caught the public's imagination and became a catalyst for the rise of "underground" youth culture even as it definitively established rock as a medium worthy of adult treatment.

At the same time, it served notice that the counterculture constituted a mass audience that could spell big money for the music biz on an unprecedented level. The 1968 documentary of the festival had more than a little to do with the mainstreaming of that notion.

Monterey Pop was brought into being by John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas, his producer and label boss Lou Adler, Beatles publicist Derek Taylor, and promoter Alan Pariser. Their vision was to elevate rock to the same level of respect enjoyed by jazz and folk (both genres already had their own Monterey festivals). And they wanted to do it in a bigger and better way than anyone had ever conceived up to that point.

Incredibly, the event was organized in less than two months, which ought to have been a recipe for disaster. Phillips and company worked around the clock: The film features telling scenes of John and his wife and bandmate Michelle Phillips mired in a dizzying swirl of phone calls and chaos. Somehow, they pulled the whole thing together in time, and without any problems.

Watch the Official Trailer for 'Monterey Pop'

Documentarian D.A. Pennebaker, already known for his cinema verite Bob Dylan film Don't Look Back, and his crew capturing the festival for posterity between June 16 and 18. While some of the artists were already stars (the Mamas and the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, Eric Burdon and the Animals, the Association, the Byrds) the Monterey also helped to break the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, and the Who, artists whose appeal up until then was on more of a cult level, at least in the States.

Yet for all the now-legendary names that took the stage at Monterey, there were nearly as many who dropped out for one reason or another. Dylan, the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Dionne Warwick, the Kinks, and Donovan were just a few of the acts that ended up missing out on the experience. At the same time, there were at least a couple of artists (the Paupers, Beverly Martyn) whose appearance at the event did little or nothing for their careers, maybe because they weren't featured in the movie.

Screen time in Pennebaker's documentary was a major bone of contention for a number of acts. Some complained that they were pressured to sign releases for the filming literally on their way to the stage. The proceeds from the festival itself were going to charity. Monterey Pop was a trailblazer in this regard, as well. Still, it was assumed that the for-profit film could wind up meaning big bucks. For this reason, a number of artists refused to sign off – whether out of objection to profiteering or fear of being exploited.

The San Francisco bands were often the ones who had a problem with the filming, highlighting the contrast and conflict between the Bay Area and Los Angeles contingents. At the time, the San Francisco scene was still basically an underground phenomenon: Monterey helped bring it into the light.

Hardcore hippies like Moby Grape and Big Brother were against being part of the documentary. Intense last-minute negotiations ended up with Big Brother finally consenting, and the decision of course turned out to be huge for their career. Moby Grape refused, however, and an angry Adler relegated them to an afternoon performance slot instead of one of the coveted evening sets.

Watch Janis Joplin Perform 'Ball & Chain' at Monterey

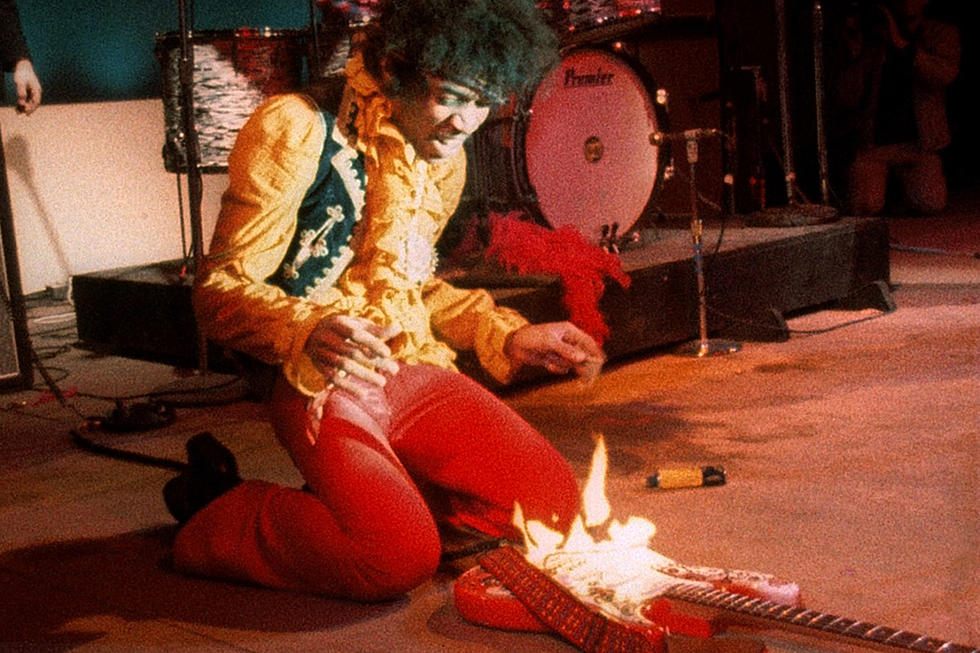

In the end, the performances that actually appeared in the documentary ended up accounting for less than half of the artists involved. Yet Monterey Pop was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. The (literally) fiery theatrics of Hendrix and the Who, as represented by the former's "Wild Thing" and the latter's "My Generation," contributed to barnstorming sets that pretty much annihilated almost everything else that weekend in terms of visceral impact.

The budding Bay Area scene was represented by a soul-wracking "Ball 'n' Chain" by Big Brother, with their singer Janis Joplin damn near leaving her spleen onstage; the brain-melting psychedelia of Country Joe and the Fish's "Section 43"; and Jefferson Airplane's journey from the ominous "High Flying Bird" to the lambent of "Today." Canned Heat's rough-and-ready take on "Rollin' and Tumblin'" gave both the blues and the L.A. scene their day.

The Mamas & the Papas were an L.A.-based group too, but by that time, their blend of pop and folk-rock had already passed its peak of popularity and no longer seemed to stand for the core of what was happening in L.A. Nevertheless, "California Dreamin'" and "Creeque Alley" showed off their considerable vocal firepower.

Simon & Garfunkel's giddy urban pastoral "The 59th Street Bridge Song" stood up for the New York folk crowd. Shankar's hypnotic raga "Dhun" and the surging Afro-jazz of Hugh Masakela's "Bajabula Bonke" more or less introduced the whole concept of world music to U.S. audiences. After the smoke cleared from the Who and Hendrix sets, Redding's "Shake" and "I've Been Loving You Too Long" practically ripped a hole in the space-time continuum with their sheer soul power.

Woodstock may have achieved a more iconic legacy and boasted an audience more than four times the size, but Monterey was where the magic of the '60s rock scene really coalesced for the first time. Decades down the road, that golden moment still shines brightly.

Top 25 Psychedelic Rock Albums

See Who Drummer Keith Moon’s Craziest Antics