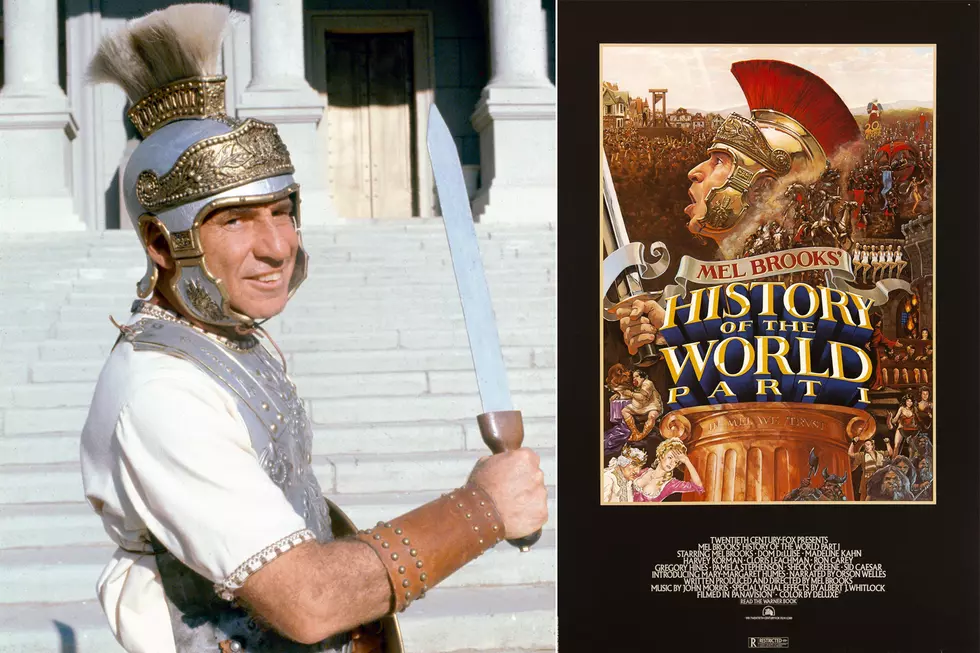

Revisiting Mel Brooks’ Juvenile Epic ‘History of the World: Part I’

With comedy legend Mel Brooks stubbornly refusing to slow down at the age of 96, the Hulu series sequel History of the World: Part II is set to release on March 6. A long, long time in coming, the series, sees Brooks acting as writer and executive producer alongside Nick Kroll, Ike Barinholtz, Wanda Sykes and a true murderer’s row of big-name comic talents born after Brooks’ comedy career was already infamous for pushing buttons and evoking belly laughs.

That History of the World: Part II exists at all is a testament to the lasting power of a good parting gag, as Brooks’ 1981 film History of the World: Part I ended with a throwaway joke about a promised sequel featuring such quick-hit premises as “Hitler on Ice” (with an ice-dancing fuhrer) and the speculative Star Wars-style spectacle of “Jews in Space.” As Brooks claimed time and time again, there was no History of the World: Part II in the offing, a statement seemingly backed up by the film’s relatively lackluster box office performance. (The $10 million film grossed a respectable $30 million, but so-so reviews and the blockbuster successes of Brooks’ previous Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein saw History of the World: Part I judged as something of a misfire.)

Looking back now that the indefatigable Brooks has finally chosen to continue his typically irreverent tour of world history, History of the World: Part I is indeed a step down from Brooks' indisputable classic comedy period — but not a disastrous one. The Mel Brooks version of a historical highlight reel breaks down into five era-hopping sketches, ranging from just a few minutes (segment “The Old Testament” consists merely of Brooks’ Moses fumbling the God-dictated commandments, costing the faithful five rules to live by) to an ancient Roman interlude that takes up the entire middle section of the movie. Indeed, there’s so much going on in the Roman section that one suspects that Brooks envisioned setting an entire feature there before running out of gas.

One of the film’s most endearing gags is the concept itself, with the idea of a millennia-spanning Hollywood epic being entrusted to Mel Brooks. The film begins with the majestic 20th Century Fox fanfare, fading into a windswept ancient vista (most of the film’s sets are made up of impressive and cost-effective matte paintings by Hollywood legend Albert Whitlock), only broken by the stentorian tones of narrator Orson Welles. That all this self-impressed setup provides the launching pad for a 2001: A Space Odyssey parody in which proto-human ape men graphically discover the joys of unbridled masturbation sets the Brooks tone perfectly, an onscreen legend reading “Our forefathers” projected over the spectacle of the spent and spasming creatures sprawled in the dirt.

“The Stone Age” continues the dichotomy between Welles’ deadpan narration and the irreverent slapstick, as caveman Sid Caesar (Brooks’ former TV boss on Your Show of Shows) discovers, in quick succession, fire, music, art and warfare, all in wordless, knockabout set pieces. (It’s essentially the same year’s Ringo Starr-starring Caveman, played out in just six minutes.) After the flag-planting juvenile gag of the opening segment, this piece lays out Brooks’ blueprint for the film, gags coming fast and from any direction, without any particular unifying theme or point of view other than what Brooks found funny. It’s not a bad template to work from, especially considering it’s Brooks, but it does function to diffuse the film’s impact. If there’s a pointed joke in this segment, it’s Brooks’ broadside against the critics that dogged him throughout his career, as Caesar’s cave-painting pioneer is immediately beset by the world’s first art critic, who whizzes all over Caesar’s proudly presented stag. Termed “the inevitable afterbirth” of the birth of art, said critic gets his later, when Caesar, conducting the first symphony, directs the stone-wielding percussionist to whack the bearded fellow repeatedly in the nuts.

After the Old Testament butterfingers gag (high-res has allowed us to determine some of the lost commandments), the Roman outing is closest to a complete story, and the closest to resembling where Brooks’ film career would go from here. It’s not that this section is bad — the inclusion of the Brooks regular Madeline Kahn as Empress Nympho is as outstanding as you’d expect — it’s more the piece shows the limitations of Brooks’ anything-for-a-gag style when it comes to sustaining an entire feature. A few absurdist jokes (a Black citizen walks through the Roman plaza playing “Funkytown” on a boombox) come across as generically “wacky,” while Brooks’ reliance on a stable of old-school schtick comics (Charlie Callas, Henny Youngman, Shecky Greene, Fritz Field) sits uneasily alongside the hip irreverence that emerges once Brooks’ “stand-up philosopher” hero meets up with Black slave Gregory Hines.

Hines, in his first movie role, was a last-minute replacement for Richard Pryor, whose infamous burning incident took place just days before he was to take on the role of smooth-talking sidekick Josephus. Pryor, who’d written on Blazing Saddles, would have been funny, but Hines is assured and slyly hilarious, channeling some of Cleavon Little’s Sheriff Bart as he runs rings around the Roman squares (and squares). As he, Brooks’ Comicus and Barney Miller’s Ron Carey (as Comicus’ agent Swiftus) are forced on the lam following Comicus’ disastrous set for the hedonistic Emperor Nero (Dom DeLuise, relishing in gross-out fat jokes), they pick up a stray vestal virgin (Mary-Margaret Humes), don various disguises and wind up foiling the pursuing centurions, thanks to Hines’ fashioning of the world’s biggest joint. (“Wacky weedus!” Josephus exclaims, furthering Brooks' assertion that adding a “-us” to the end of words is side-splitting stuff.)

As the film centerpiece, the Roman section functions as an amiably rude mini-feature, Brooks’ stabs at his usual snickering vulgarity coming off best in the hands of Kahn. (Auditioning bare-bottomed centurions for that night’s orgy sees her Empress Nympho belting out an appreciative song as she surveys the goods, Kahn giving us a full-throated “Yeeeeessss!” upon seeing one particularly impressive specimen, echoing her turn in Young Frankenstein.) Likewise, Hines’ cool Black-guy routine echoes Blazing Saddles, but in a milder key, the segment’s social commentary boiling down to throwaway gags like Comicus and Josephus attempting to hide out in the Roman Senate while murmuring, “Bullshit, bullshit.” When, upon escaping the city, the four protagonists break into a riff on the Hope-Crosby Road films, it’s evident the sort of breezier tone Brooks had in mind.

Watch the Trailer for 'History of the World: Part I'

That this segment ends with an innocuous scene where Comicus is the waiter at the Last Supper of John Hurt’s Jesus might be pleasantly cheeky, but “The Spanish Inquisition” is anything but. Brooks channels his “Springtime for Hitler” The Producers showstopper here, as Grand Inquisitor Tomas de Torquemada (Brooks) bursts into a full-scale Busby Berkeley song and dance, complete with tastefully disrobing nuns performing a water ballet, all while stereotypically costumed Jewish prisoners are tortured all around. It’s the sort of big swing that Mel Brooks would take to sate his desire to pay homage to old Hollywood while simultaneously pissing people off. (Indeed, several Jewish groups were vocally less than amused at the sight of the auto-da-fe being turned into a zippy musical cavalcade.)

While Whitlock’s matte work kept the scenery budget low elsewhere, Brooks spent nearly a 10th of the film's budget on the practical inquisition set, complete with a hidden swimming pool, human slot machines and elaborate torture devices. Was it worth it? As an intended showstopper, the segment lives up to the name, although, as the gag plays out, that stop becomes more of a grinding one. Brooks wanted to shock both those sensitive to what the Inquisition’s religious genocide was, and audience members perhaps not as into old-school Hollywood parodies as he was, and that’s where “The Spanish Inquisition”’s strength lies, more than the actual comedy itself.

Concluding Brooks’ scattershot tour of history’s most mock-worthy eras is “The French Revolution,” where Brooks’ King Louis XVI debauches his way right into a peasant uprising. Brooks regular Harvey Korman is on hand as the king’s devious right-hand man, the Count de Monet, whose repeated correction of his name’s pronunciation (it’s not “Count de Money”) rehashes the same Hedy/Hedley Lamarr gag from Blazing Saddles. (Korman’s lecherous henchman also winds up molesting a stone statue, just as Lamarr does.) With Brooks pulling double-duty (he’s also unfortunate lookalike lackey le garcon de pisse, tasked with impersonating the king when not toting buckets of aristocratic urine), the segment is the most assured of the lot. Brooks’ Louis coins his catchphrase, “It’s good to be the king,” straight to the camera after casually mounting his mistress in the royal gardens, while the poor piss boy is confronted with not just the looming guillotine but also the king’s latest conquest, a desperate virgin bargaining for her imprisoned father’s life. (Future Saturday Night Live cast member Pamela Stephenson, displaying as much comic energy as cleavage.)

As with much of the jokes throughout History of the World Part I (and Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein), the juxtaposition of period setting and modern-day vulgarity gets most of the laughs. “You look like the piss boy!” du Monet exclaims upon seeing the lowly potential replacement, to which Brooks’ Luis responds indignantly, “And you look like a bucket of shit!” Similarly, there’s a lot of self-plagiarism in Brooks’ film, with lines, gags and characters (including Cloris Leachman’s wild-eyed, accented Madame Defarge) calling up old laughs from other, better Brooks films. But perhaps History of the World: Part I’s greatest failing is how Brooks’ unfocused take on his grand subject recedes in the memory.

Monty Python’s Life of Brian might have opened the door for this sort of grandly silly epic historical comedy a few years before, but that film drew its power from how lived-in and sustained the humor’s focus was. 1980’s terminally lazy Wholly Moses! (which did feature Pryor) failed because it simply wasn’t funny, while History of the World: Part I is a joke-a-minute gag-fest, where even the biggest laughs are swamped by how slapdash Brooks’ overall construction is. It would be six years until Brooks took the director’s chair again with Spaceballs, a Star Wars riff that, for all its popularity, saw Brooks’ penchant for low-hanging and obvious gags sink even lower. Here’s to an infusion of new blood reviving the Brooks of old in the long-awaited Part II.

Mel Brooks Movies Ranked

More From 107.7 WRKR-FM